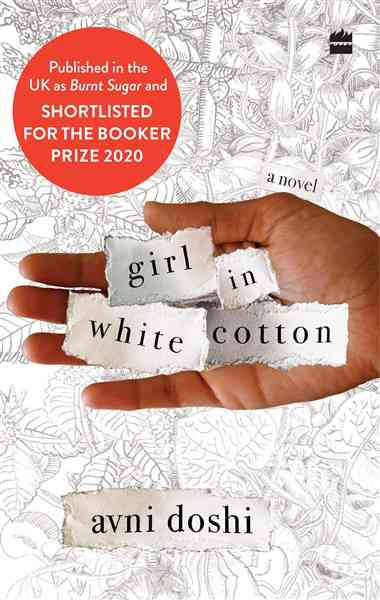

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020, Avni Doshi's debut novel, Burnt Sugar, was first published as Girl in White Cotton by HarperCollins India in 2019. The Guardian called it "an unsettling, sinewy debut, startling in its venom and disarming in its humour." Here's an excerpt to give you a taste of this critically acclaimed novel -

My earliest memory is of a giant in a pyramid. The giant sits at the centre, and he is larger than the others, taller too, because his tall body is on a platform that elevates him. He mimics the structure he sits within, and forms a large white pyramid, composed of white clothes, grey hair and a thick beard. Around him are smaller pyramids, also white, and Ma is one of them – one among a sea of pyramids – and when I look up, the ceiling of the room meets in an apex high above my head, pointing upwards to the sky outside.

The smaller pyramids, like Ma, are not as small as I am but more medium in scale. They copy the giant, sitting cross-legged, wearing white. The aim of the congregation seems to be to copy the giant. I am the smallest in the room and I don’t know how I would manage being any bigger. Some of the medium pyramids are terrifying if I get too close; they have hair and pimples, and large pores on their noses.

There is one other who is about my size, the one who sweeps the room once the giant and the sea of white are finished with it. She also wipes windows, carries food on trays, waters plants, and collects shit left by the ashram dogs. She doesn’t speak, and sometimes when I see her, she is holding a dirty rag with a frown on her face. After lunch, she rests on a patched-up straw mat, and her eyes shine through the crevices of her elbows.

The giant opens his eyes, his lower lids fall away from the upper. Hair grows all over his face, but somehow I can make out he is a man and not a beast, and Ma is not afraid so I try not to be. Three strings of beads hang around his neck – brown, pink and green – forming a tangle. I want to pull them off him and wear them myself because I have no necklace of my own, but I dare not go near him. His mouth opens and his tongue pushes out, and I can see darkness at the back of his throat, teeth covered in darkness, a never-ending recess.

I move close to Ma. She is looking at him, sweating with the rest of the room, but I can smell her particular smell, and I love her because she is known to me in some way I cannot explain.

She draws me to her and kisses me full on the mouth. Then she squeezes me into her side and tickles my neck. I am embarrassed, and wary of her affection because it’s often followed by something unpleasant.

The giant draws his tongue back in and swallows, preparing before once more pushing it out. Saliva falls a few feet in front of him, on to a medium-sized pyramid, a man with yellow hair, but the yellow-haired pyramid does not move – he is mesmerized and copies the giant, sticking his tongue out of his mouth, and a light spray of spit falls just beyond his shadow. I look around and my mother and all the other pyramids are following. The giant laughs or coughs, I am not sure which, and laughs and coughs more, in a continuous stream, and his belly, which sits a little in front of him, is shaking and his hair is bound into tentacles. The rest of the group follows, coughing, laughing. I even hear a belch. A woman beside me starts to cry, but when I look at her, no tears are falling down her face.

The room smells warmer, like my finger when I rub it in my navel.

The woman beside me screams between her cries, and some other pyramids scream in response. I look at Ma and her face is red from coughing. I hold her hand, but she pulls it away and begins to stand, and I see that the giant is also standing and all the medium-sized pyramids are transforming themselves into white columns.

I stand and hold on to the edge of Ma’s kurta, curling it in my hand, working my fingers against the white fabric.

The giant has lifted his arms and is shaking them, and they wiggle and fly away from his body as though he is loosening, as though he is going to let his limbs go and give them to the sea of white, the way he gave his breath and his saliva.

The ground is moving because they are moving – all the pyramids, jumping, stomping, dancing, holding each other. Someone taps me on the forehead, and someone gathers me into her arms. I cry for Ma but I cannot see her for a moment, until I find her behind me. Her breasts are bouncing below her white kurta, and the sea of people envelops her, fondles parts of her body and releases her once more.

The giant is croaking and his eyes bulge, and his face is like a frog’s. He croaks again and again, and some follow him, adding to the croaking, but others heave their bodies around like different animals, neighing, bleating, bringing up sounds from inside themselves that are unfamiliar to me. They are all around me, closing in and receding, and I sit on the ground and they seem to forget I am there, but I can smell the skin of their feet as it rubs against the tiled floor.

Ma, I think to myself as I watch her. I want her to look at me but she is elsewhere. I can see it in her face, a face she wears when she cannot see me. I don’t know where I have seen this face before because I can’t remember what came before it, but it is familiar and something I know to fear.

Ma has her arms in the air and is spinning around in circles. There are two men on either side of her and she disappears between them as they dance. She stops turning and teeters here and there, and one of the men holds her steady, laughing, but her hair is stuck to her head and her mouth falls to one side, still finding its balance. Others are shouting, retching, crying out at the top of their lungs, charging the air with nonsensical sounds.

‘Ma,’ I say.

Write a comment ...